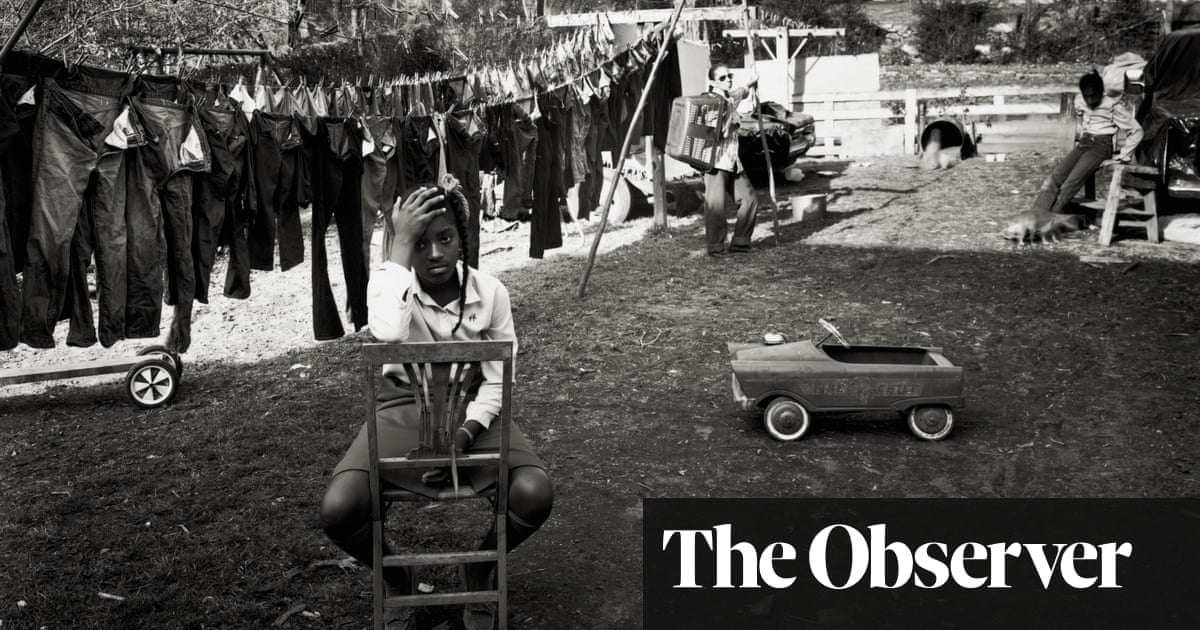

You can see a whole world – submerged, waiting, ready to burst forth – in the face of any adolescent girl. In Sally Mann’s At Twelve: Portraits of Young Women, she captures this special, unstable time of life. In this image, a plaited-haired girl sits in a chair, head in hand like a world-weary grownup. This is Olivia, “with that ruined prayer in her eyes”, as Mann describes her. In the background, a phalanx of dark trousers hangs from two washing lines that cut across the image and lead our gaze towards her grandmother, who dangles the now-empty plastic laundry basket over one shoulder.

“This is just half the day’s laundry,” Mann tells us in a loose narrative that runs through a reissue of the well-known 1988 publication by the artist notorious for capturing girls on the threshold of womanhood with unnerving perspicacity. The youthful gamines, locals of Mann’s own back yard of Rockbridge County, Virginia, are by turns funny, glamorous, knowing, evasive, worried, rich, poor, babyish, frighteningly mature – all of the complexities we know girlhood and its projections to hold, but sometimes find difficult to behold.

Like the other 12-year-olds pictured in the book’s arresting black and white photographs, Olivia looks us dead in the eye, as if to ask what we are looking at while quietly ceding to the photographer’s curious lens. She is one of more than 10 children living with her grandmother, her father unknown, her mother gone. Where? “She travels,” grandmother says, conjuring an ethereal, roaming figure, lost somewhere unknown. An unmanned toy car sits battered and unmoving near the centre of the image like a ghostly prop. Olivia may travel, too, someday, but for now she is frozen in place – like the subjects of all photographs – as time telescopes in both directions, promising everything and nothing. “We are their mirror, they are ours,” the short story writer Ann Beattie observes of these girls on the brink in her introductory essay. It’s Olivia’s world, we’re just living in it.