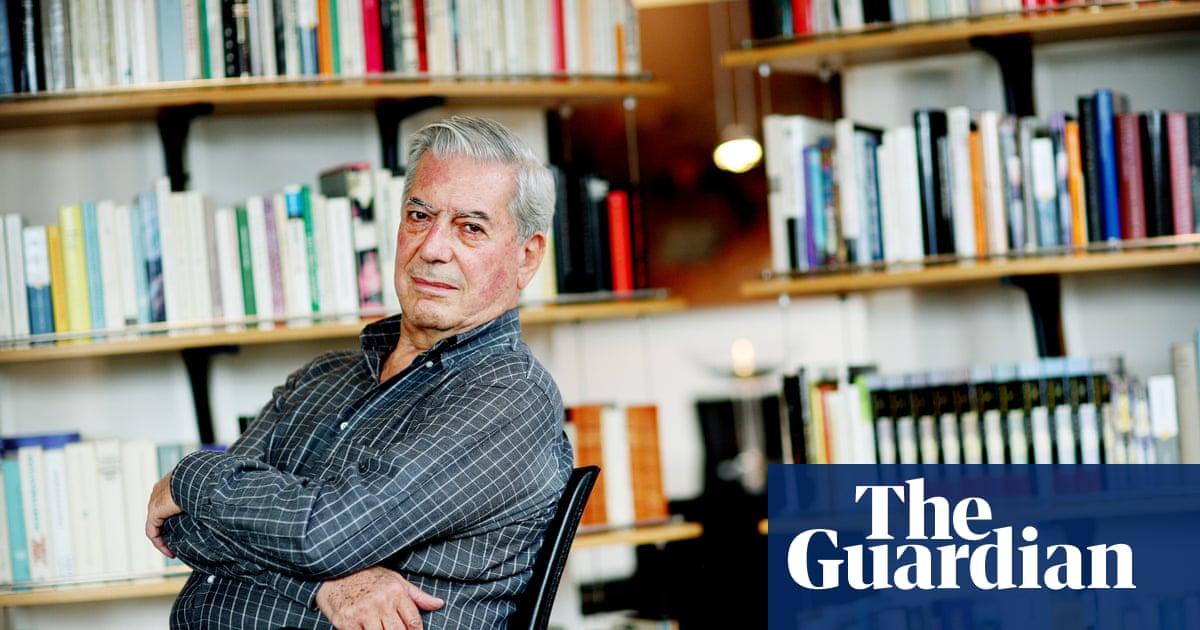

Many Latin American writers have been tempted to take on a public role, but few have pursued this ambition as far as the Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, who in 1990 came close to being elected his country’s president. Vargas Llosa, who has died aged 89, owed the possibility of high office almost entirely to his novels, which put him at the forefront of world writers for more than 50 years.

His early works, such as The Green House (1966) or Conversation in the Cathedral (1969), firmly established him as one of the leading authors of what came to be known as the “magical realism” school of writers, although in his case this was often more a question of novelistic technique than of any magical view of his country’s history. He also developed a comic vein most evident in Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977) that also set him apart from other writers of the so-called “boom” in Latin American fiction.

Vargas Llosa said that the urge to write came from the unusual circumstances surrounding his childhood. Born in the southern Peruvian city of Arequipa, he was sent by his grandfather, with his mother, Dora Llosa, brothers and sisters, to live in neighbouring Bolivia when his father, Ernesto Vargas, abandoned the family. The young Mario grew up believing his father was dead.

When he was 10 his mother presented him to a complete stranger, and told him this was his father. Ernesto rejoined the family, and they lived together in the Peruvian capital, Lima. Recalling this difficult relationship in his autobiography A Fish in the Water (1993), Vargas Llosa spoke of the “social inferiority” his father felt towards his mother, and calls it “the national disease … the one that infests every stratum and every family in the country and leaves them all with a bad aftertaste of hatred, poisoning the lives of Peruvians in the form of resentment and social complexes”.

The rancorous complexities of Peruvian life were brought home still more forcefully to the adolescent Mario when at the age of 14 he was sent to a military academy. He hated the harsh discipline, but it enabled him to meet people from different backgrounds and regions. The experience formed the subject matter of his first novel, The Time of the Hero (1963), and informed several of his later works.

Vargas Llosa was well aware by now that it was literary rather than military glory that he was destined for. By the age of 16, he was working as a crime reporter on a daily newspaper, and at 19 he eloped with his much older aunt by marriage, Julia Urquidi, whom he married in 1955. Once again, he turned this to good literary effect in Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, about a radio soap opera hack who finds it increasingly difficult to separate reality from his fictional creations. This was the only one of Vargas Lllosa’s books to attract Hollywood’s attention. William Boyd, the writer of the screenplay for the 1990 film (released in the US as Tune in Tomorrow), described the original as “almost Swiftian, with a quality of fantasy that sees the world as lurid and absurd”.

After graduating from the National University of San Marcos, Lima, in 1958, Vargas Llosa was living in Europe, either in Barcelona, London or Paris. At that time, the French capital was thronged with young Latin American writers – including Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar and Carlos Fuentes – and it was the French publishing houses who first created the boom in Latin American literature. The young Peruvian novelist was warmly welcomed as a member of this literary club.

Vargas Llosa’s novels of this period are closer to the realist tradition of the novel than to “magical realism”, providing as they do incisive descriptions of many levels of Peruvian society. The magic consisted in the novelist’s skill of combining different narratives and voices without explicit connections, offering a rich complexity and suggesting a huge literary appetite.

These early novels contained a sweeping criticism of the state of Peruvian and, more widely, Latin American society. The younger generation of writers took the political dimension of their work extremely seriously, and it was understood that they shared a leftwing viewpoint. Mario soon came to be seen as the odd man out. As so often, it was Fidel Castro’s revolution in Cuba that was the flashpoint. When Libre, a pan-Latin American magazine was launched in Paris, it was not long before Vargas Llosa, García Márquez and others quarrelled over whether to support Castro.

Vargas Llosa consistently adopted a liberal attitude, and never accepted that any difference should be made between developing countries and Europe, the US or other representative democracies. His combative defence of this position earned him enemies among the left in Peru and the rest of Latin America, where it has often been argued that writers ought to be on the side of the majority of poor and downtrodden, providing them with a voice they are denied.

Through the next decades, Vargas Llosa continued to publish novels that won him success and critical attention throughout the world. Some, like The Storyteller (1987) or Death in the Andes (1993), suggest he was attempting a Peruvian version of Balzac’s multi-volume collection La Comédie Humaine, trying to encompass the whole of Peruvian society in his works. But, as he made plain in the critical work The Perpetual Orgy (1975), his personal preference was for another French master, Gustave Flaubert, for his modern spirit, his sense of irony and his intense preoccupation with language and style.

Vargas Llosa’s international reputation led the Peruvian government to involve him directly in political matters in his home country. In 1983 he was asked to help investigate the killing of eight journalists in the remote Andean village of Uchuraccay. This occurred at the height of the struggle between Shining Path guerrillas and the Peruvian armed forces, and Vargas Llosa once again infuriated the left in Peru and elsewhere when he agreed with the official version that the villagers had mistaken the journalists for guerrilla fighters and killed them, rather than insisting that the blame lay with the security forces.

His move to rightwing liberalism also came from his voracious reading. It was French historians such as Fernand Braudel who convinced him that the development of markets and the possibility of trading in the Middle Ages was fundamental to human nature. He found further confirmation of his political philosophy in the careers of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, whom he fervently admired.

Once more, Vargas Llosa translated these beliefs into action in his native Peru. When in 1986 the leftwing populist government under Alan García declared its intention to default on the country’s foreign debt and to nationalise the banks, Vargas Llosa began a protest campaign in the name of individual freedom. It was this campaign that fed his presidential aspirations. In 1989, he presented himself as candidate for a variety of rightwing and centrist parties, campaigning on a conservative free-market ticket. He brought in campaign managers from Britain and set about using his writing and speaking skills to win over the Peruvian electorate.

Unfortunately, it was plain from attending his political rallies that, although he might imaginatively understand the situation of hugely different sectors of Peruvian society, he did not have much idea of how to speak to them directly. Despite this uneasiness, he won most votes in the first round of the presidential election and was confident of winning the second round against an unknown Peruvian-Japanese agronomist, Alberto Fujimori.

In the weeks between the two rounds of voting, however, Fujimori gained increasing support from poor Peruvians who saw in the light-skinned, cosmopolitan Vargas Llosa exactly the same kind of ruler who had been making unkept promises to them for several hundred years. Eventually, it came as little surprise that it was Fujimori who won. Vargas Llosa quit politics, unable at first to believe that he had been rejected in this way.

His bitterness surfaced in Death in the Andes (1993), in which he portrays Peru’s Andean society as so backward that it is capable of cannibalism. Around the same period, he withdrew to a more intimate fictional world, exploring the possibilities of eroticism in In Praise of the Stepmother (1988) and The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto (1997).

Although no longer directly involved in politics, Vargas Llosa used his journalistic skills to lambast the Fujimori regime, especially following the “auto-coup” the president engineered in 1992. Vargas Llosa complained that by way of reprisal, the authorities demolished his Lima home. This led him to renounce his Peruvian citizenship, and in 1993 he took Spanish nationality.

The Feast of the Goat (2000) is his outstanding contribution to a long tradition of Latin American novels examining the abuses of power by dictators in the region. It deals with the Dominican Republic’s dictator Rafael Trujillo, and the moral, sexual and political corruption implied by authoritarian rule. “I wanted a realist treatment of a human being who became a monster because of the power he accumulated and the lack of resistance and criticism … Converted into a god, you become a devil,” Vargas Llosa commented of what many saw as his finest book.

He continued to explore subjects outside Latin America that were nevertheless linked to Peru. The Way to Paradise (2003) concerned not only Paul Gauguin in Tahiti, but also the artist’s grandmother, Flora Tristan, an early revolutionary feminist in Peru. His 2010 novel The Dream of the Celt is a fictional account of the life and death of Roger Casement, whose views on slavery and colonialism were radicalised by his experiences during the time he spent living in the Peruvian Amazon.

In that same year, Vargas Llosa was awarded the Nobel prize for literature. His acceptance speech was a passionate defence of fiction and reading, insisting that “without fiction we would be less conscious of the importance of the freedom that makes life liveable, and the hell it becomes when it is constrained by a tyrant, ideology or religion”.

He had previously (in 1994) been the recipient of the Cervantes prize, the highest honour for writers in the Spanish-speaking world. In 2011, his friendship with the Spanish king Juan Carlos resulted in his being given the title of Marquis of Vargas Llosa.

He and Urquidi divorced in 1964, and the following year he married his cousin Patricia Llosa. In 2015 he separated from her, and publicly announced his relationship with the socialite Isabel Preysler, much to the delight of the gossip magazines.

The Neighbourhood (2018) is a steamy tale of the Peruvian jetset featuring blackmail by such a magazine. Their relationship ended in 2023, Vargas Llosa saying he wanted to devote more time to literature.

His novel Tiempos Recios (2019) was his last to be published in English, as Harsh Times (2022). It examines a historical event, in this case the CIA-backed coup against the Guatemalan government in 1954, through a fictional account.

In addition to novels, Vargas Llosa wrote extensively for the theatre, and acted in several of his own plays. He once told me in an interview, when asked what he thought would make a suitable epigraph for him: “He lived life to the full, and loved literature above all else.”

He is survived by a daughter, Morgana, and two sons, Álvaro and Gonzalo, from his second marriage.