Not every artist who skyrockets to fame makes it all the way into space. But that was the case for Amoako Boafo who, three years after his big break, painted three panels on the top of Jeff Bezos’s rocket ship. “I’ll be honest, I just did it for the experience,” says the Ghanaian artist, whose triptych blasted off in August 2021 and returned (intact) after an 11-minute round trip. If the opportunity should arise, would he ever be interested in taking a tour himself? “No, I like it here,” he replies, tapping the ground with his green Dior trainers.

Boafo’s artistic breakthrough came when his effervescent portraits celebrating Black life caught the eye of Kehinde Wiley on Instagram in 2018. Wiley, the African American artist best-known for painting Barack Obama, tipped off his galleries, and before long Boafo’s canvases, which he began exhibiting in hotel lobbies back home in Accra, were appearing at international art fairs and fetching up to seven figures at auction. A spring/summer collection in collaboration with Dior designer Kim Jones followed in 2021, and in 2022 he was picked up by mega-dealer Larry Gagosian, who has referred to him as “the future of portraiture”. His first solo UK show has just opened at Gagosian’s largest London outpost.

“For me, this exhibition is a gentle reminder of what I want to do when I step away,” says Boafo in the gallery, over the whirr of nearby construction work. The opening is three days away when we speak, and yet it’s still very much a work-in-progress, with paintings leaning against the walls and the courtyard of Boafo’s childhood home mid-recreation next door. Returning our gaze are the artist’s friends and family, as well as five of Boafo’s self-portraits – pedalling on an exercise bike, lounging in bed, embracing his young son. These are more self-portraits than he’s ever included in a single show. “I want to remind myself that I don’t always have to be out there, rushing around.”

Born in 1984, Boafo grew up in Accra. His father was a fisher, and his mother cooked and cleaned. From a young age, he found art to be a respite: “Whenever I would sit and draw, I wouldn’t think about anything else; it was as if there were no problems.” He was as nifty with a racket as he was with a pencil, and believing that he might have a better shot at earning a living as a tennis player, he threw himself into the sport while studying art on the side. “I managed to convince myself that I was going to make money from tennis and that when I retired I could paint,” he says. But after four years at the Ghanatta College of Art and Design he found he enjoyed painting more. I ask him if he still plays tennis, and he inches up the hem of his trousers to reveal a pair of Nike socks. “I don’t see anyone who’s 40 years old in this world beating me.”

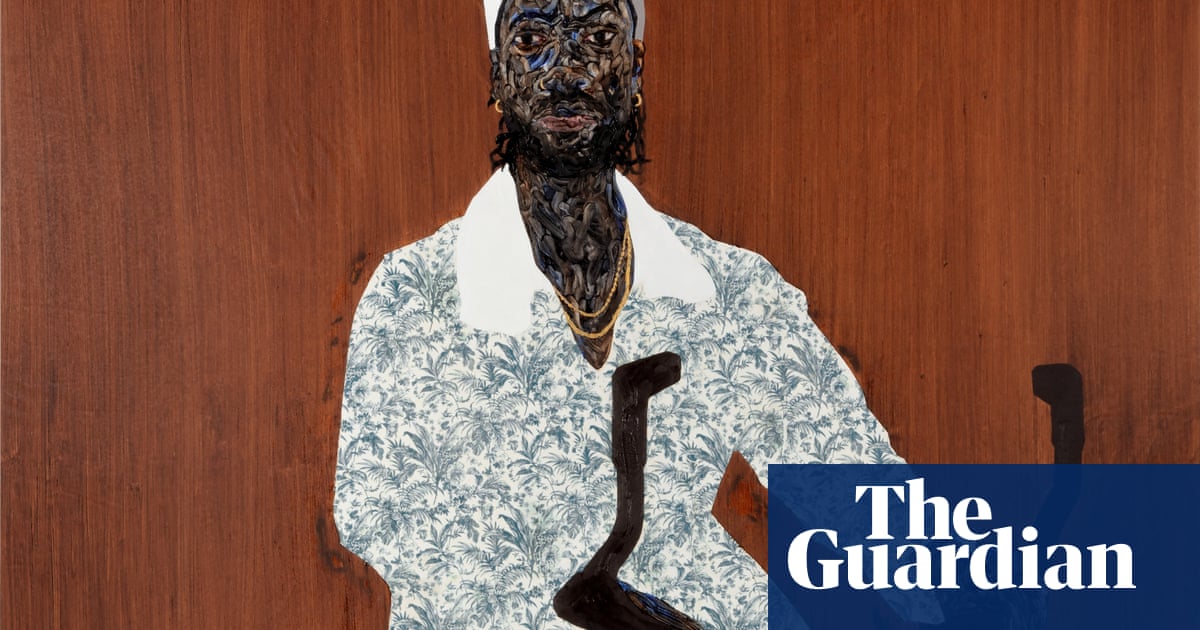

In 2014, Boafo moved with his partner to Vienna, where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts. “At first I had all this space and time, and I didn’t know what do with it,” he says, comparing it with the more supervised teaching he was used to at home. Surrounded by white faces, he decided to focus solely on Black subjects. Poised between figuration and abstraction, his expressive portraits are at once rooted in tradition and wholly contemporary, borrowing from Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele as much as Toyin Ojih Odutola and Amy Sherald. What sets them apart is the technique that has become synonymous with his name: modelling the skin of his sitters with his fingertips.0

“I mean, it’s not as beautiful as painting with a brush, but it allows me to be more playful,” he says, as we stand up and stroll around the room. “With fingerpainting you have no control, and I like the challenge. You can’t go over it – if you do, it’s kaput.” Up close the effect is mesmerising: ripples of bright blue and brown appear to pulse, blood-like, along his sitters’ limbs, lending them a sense of vitality that’s hard to shake. The poses are static, but contained within the smears and swirls of a single hand – even an ear – is a rhythmic movement, a fizzing energy.

Some backdrops are plain, others patterned with the same wrapping-paper designs that appear on the sitters’ clothes. At first, Boafo used African fabrics, but the majority here came from Vienna. “I love fashion,” he says, in case I couldn’t tell from the cream-coloured baseball cap (also Dior), “and after a while I realised I could just make my own prints and dress someone the way I want them to look or according to how I feel and what I want to say.” Unusually for Boafo, he isn’t wearing anything patterned today, but his green overshirt and trainers echo the zingy palette of a large self-portrait featuring lush potted plants. “I like to look like my paintings,” he says. “It’s not like I paint one way and then have a different character. The way I live is the way I paint.”

By now, the drilling has stopped, so we head next door to see how his childhood courtyard is coming along. Soon it will be hung with paintings, but at present it’s bare, an abstracted artefact made from charred wood – a nod to the fire on which Boafo’s mother cooked their meals growing up. Located at the heart of most traditional residences in Accra, the courtyard is a communal space where family and friends come together. “For me, it’s a space of knowledge and learning,” says Boafo, “a space where you get to see how people live.” Like his paintings, it’s a celebration of community.

The courtyard has been recreated by architect and designer Glenn DeRoché, who worked with Boafo on dot.ateliers | Ogbojo, the writers’ and curators’ residency programme he established on the edge of Accra in 2024. As the appreciation for African art continues to grow in the west, Boafo believes that what’s needed is more education back home. “There’s a lot of talent, but we still depend on the west to collect and to maintain it,” he says. “I think there should be more education on collecting, because once we have home-based collectors, careers can be more sustainable.”

More residencies are cropping up, among them one Boafo and DeRoche are working on specifically for sculptors. Boafo also has plans for an art club – “a proper creative space where you come and just be inspired” – as well as a tennis academy and a football academy. But first, DeRoché needs to finish the court he’s building for Boafo, who wants to play more tennis. “I’m not stopping painting – I can’t,” he says. “I paint when I’m on holiday, I paint when I’m sick. Painting is part of me.”

Is he feeling the pressure that comes with being the so-called future of portraiture? He says it’s inevitable, but that to be in the position he’s in is a dream come true.

“So, yeah, I will complain about the stress, but I can take it, I’m good.”