It has come to this: we are now in Ministry of Truth territory. In Washington DC, the Smithsonian Institution, the US’s ensemble of 21 great national museums, last week became the subject of an executive order by President Donald Trump. “Distorted narratives” are to be rooted out. There will be no more of the “corrosive ideology” that has fostered a “sense of national shame”. The institution has, reads the order, “come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology” that portrays “American and Western values as inherently harmful and oppressive”. The vice-president, JD Vance, is, by virtue of his office, on the museum’s board. He is charged by Trump to “prohibit expenditure” on programmes that “divide Americans based on race”. He is to remove “improper ideology”. The order is titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History”. George Orwell lived too soon.

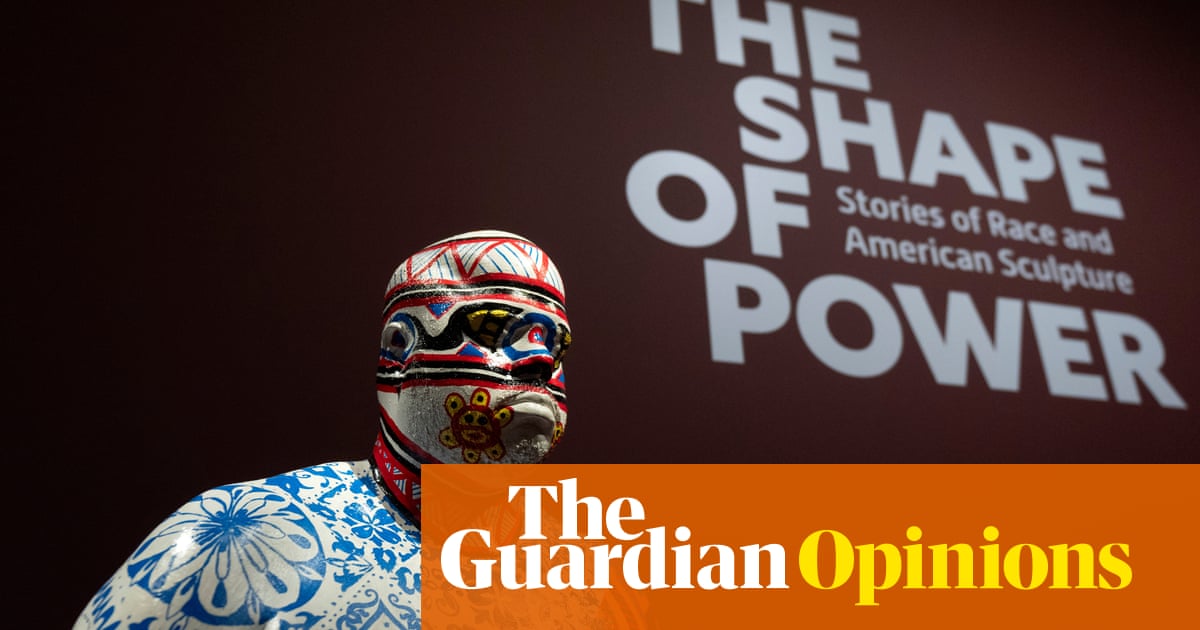

The move is deeply shocking, but predictable. After Trump’s insertion of himself as chair of the John F Kennedy Center and his railing against the supposed wokeness of the national performing arts venue, the federally funded Smithsonian was bound to be next in line. Those who imagined the Kennedy Center was a one-off, attracting the president’s ire for personal reasons, were deluding themselves about the scale of Trump’s ideological ambition. Picked out for opprobrium in the executive order are the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum for celebrating transgender women (the museum, it should be pointed out, has yet to be built); the National Museum of African American History and Culture; and an exhibition titled The Shape of Power: Stories of Race and American Sculpture at the American Art Museum.

I visited the Museum of African American History for the first time a couple of weeks ago. It is a vast book of a museum, heavy with text. It was full, when I visited, of mostly Black families seeking out an encounter with a narrative that has long been a footnote to, or erased completely from, the main national story. You could spend days absorbing the web of stories that the museum offers, beginning in its basements with the transatlantic slave trade, where one of the most moving objects is, unexpectedly and profoundly, a piece of iron ballast that took the place of a human body after a ship’s cargo of enslaved people had been disgorged on the triangular route between Africa, the Americas and Europe. The whole strikes a fascinating balance between an unflinching gaze on systems of oppression, and a sense of Black achievement and cultural richness that has nevertheless effloresced.

Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the museum, gave a talk at the House of Lords in 2011 about the institution, which was still in the planning, and would open five years later. I can still recall how moving it was to hear about the difficulties of making a museum – a place where a story is told through objects – from communities traditionally poor in material things. The institution had put out a call for loans and donations. Precious, carefully treasured objects – a bonnet embroidered by someone’s enslaved grandmother, for example – were arriving into the new collection.

Fast forward to the present, and Bunch is in charge of the entire Smithsonian Institution. This is a man who believes, as he told Queen’s University Belfast last year, that history can be used to “understand the tensions that have divided us. And those tensions are really where the learning is where the growth is, where the opportunities to transform are.” That compassionate vision of the past, as a means through which the citizens of the present can better understand each other, is completely opposed to the monolithically triumphalist spirit of Trump’s executive order, in which history is reduced to “our Nation’s unparalleled legacy of advancing liberty, individual rights, and human happiness”. How much easier it is, to sink into this pillowy, comforting notion of glorious progress than to grapple with the kind of knotty, often upsetting and confronting history that the Museum of African American History offers its visitors. But it makes me wonder: can the museum survive this government?

I visited, too, the American Art Museum, whose show The Shape of Power is targeted in the executive order as emblematic of the Smithsonian’s decline into “divisive, race-centered ideology”. The exhibition, which was years in the careful making, points out what is surely obvious, once it has been given a moment’s thought: that race is not an inherent and prepolitical category, but rather a constructed set of ideologies that served (and still serve) a set of economic and political interests. (One way to tell that race is a socially constructed category, in fact, is by looking to the Greeks and the Romans – the people who established, in the minds of many on the US right, “western civilisation”. They were xenophobic in their own way, and enslavement was a fact of their societies. But as is obvious from their literature, whiteness and Blackness were for them simply not operative categories.) The exhibition is an eye- and mind-opening look at how race ideology has translated into and been reinforced, or deconstructed, by sculpture – that peculiarly lifelike and thus “truthful”-seeming artform.

The catalogue quotes Toni Morrison, who once wrote that “I want to draw a map, so to speak, of a critical geography and use that map to open as much space for discovery, intellectual adventure, and close exploration as did the original charting of the New World.” Such intellectual adventuring is not what is wanted by the White House now. Trump’s world is more like Viktor Orbán’s, under whose government the school history curriculum has been rewritten to glorify Hungary, or Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey, where the novelist Elif Shafak, as she recalled in a Guardian Live event last week, was prosecuted for “insulting Turkishness”, her lawyer obliged to defend in court the views of her fictional characters. The Smithsonian and all who work there have an unenviable choice, one that has already been put before other great or formerly great institutions such as Columbia University: to comply with Trump’s dark demands; or to find ways to defy them.